Ilse van Rijn

Poetry as Material Intervention in Contemporary Art

In this essay Ilse van Rijn delves into the presence of poetry in visual art today and what she perceives as poetryŌĆÖs potential for restructuring (institutional) thought. This builds on van Rijn's PhD research on contemporary artistsŌĆÖ texts, texts written and produced by visual artists, and specifically the final chapter of her thesis, which investigates the relationship between artistsŌĆÖ writings and poetry, a chapter that opens the many questions and observations shared in this essay. The essay was first presented as a lecture for the programme of "The Shadow of Knowledge" an ARIAS network meet-up held in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, on 25 October 2019.

ŌĆö

Poetry permeates all segments of contemporary art. Poets give readings in art institutions and bookshops. Witness, for instance: Alex TurgeonŌĆÖs reading of his Love Poems for Ceres (2017) at San Serriffe in 2018; the event Poetry Will Be Made By All! organized by the LUMA Foundation in Zurich in 2014; Karl HolmqvistŌĆÖs exhibition for Moderna Museet, Stockholm in 2013 titled Give Poetry a Try; Poetry as Practice initiated by the New Museum, New York in which ŌĆ£ŌĆ” six poets approach internet language as a bodily, social and material processŌĆØ1; art journals Texte Zur Kunst (2016), Frieze (2014) and Metropolis M (2018) that each dedicate articles or whole issues to poetry; The New Inquiry that in 2016 states ŌĆ£poetry is having a momentŌĆØ2; writer, critic, and curator Quinn Latimer who writes the book, Like a Woman: Essays, Readings, Poems.3 These examples are diverse, ranging from an exhibition, to a publication, and a reading. They are initiated by artists and critics, curators and editors alike. The question arises, what do we talk about when talking about poetry in the realm of visual art today? What is poetry, or rather, what does poetry do? What is its operative force? What does it bring about or move? By delving into how poetry functions, I seek to gain insight into this curious assemblage of poetry within visual art today.

I have always found poetry complex. It imposes itself on you. You cannot escape it. It invades your life without you being able to fully grasp what it does, how, when, and why. Poetry unsettles; it unsettles my thought, it unsettles my day. It bears the mask of a fleeting thought, posing as ephemeral, lightweight, immaterial, casual in its fragmentary fashion. Once read, it reveals itself as dense, opaque, slow, intransigent, heavy, and thick. In the guise of language, paradoxically, any clear-cut meaning is obscured. What happens, to frame it in linguistic terms, is that poetry loosens language, to the point of breaking the traditional ties between the signifier and the signified, problematizing access to what is considered meaning or sense. As a consequence, poetry is hard to understand, at first sight at least. Or the inverse is the case; precisely due to the forced disconnection between the word and the world, the poem offers a sudden glimpse at an illuminating idea. When you try to unravel the argument and point to the thought, however, the poem falls apart. Poetry is constructed, but in an inimitable way. Poetry cannot be grasped, it cannot be reproduced (keep in mind that reproducibility is precisely the condition for scientific knowledge). Poetry, by contrast, always has to be restaged without there being any original or originating moment. In poetry, actual meaning, leading to clear and concise knowledge and answers, is repressed. Poetry is resistance.4Poetry is refusal. In the words of American poet Anne Boyer, poetry says NO.5

I continue to learn to read poetry. Especially since not all refusals are equal, and are made concrete in various ways. Not all concretisms are equal.6A poem like His MasterŌĆÖs Voice7by artist Alice Creischer, for example, is written in the form of a play in which the actors speak the language spoken during the 2014 Munich Security Conference. It consists of four characters, The Master, The Ear, The Tongues, The Voice, each with their own part in the play.

Ilse van Rijn

Poetry as Material Intervention in Contemporary Art

Alice Creischer, His MasterŌĆÖs Voice.

KOW Berlin, Nov. 24, 2018ŌĆōJan. 19 2019.

Performance view.

THE VOICE:1

Mr Ischinger, with your predecessor Horst Teltschik and the founder Ewald von Kleist, you have made the Security Conference and outstanding forum ŌĆ” a fixture ŌĆ”

what can we do but behold

we behold

this milestone anniversary

and backwe look

searching and tenderly

as if under a lantern

we look onward

and see ourselves

anew

in it

as in a pool

in the cesspoolwe

[ŌĆ”]

Footnote three, affixed to ŌĆ£The Voice,ŌĆØ refers to the opening speech of the 50th Security Conference in Munich given by Joachim Glauck. I checked the link, and it directs the reader to the speech still available online. The power structure that the poetic language epitomizes is criticized by the same gesture of the poem, as a poem, but in the poem as well. The work resembles the strategies of appropriation of institutional language in Andrea FraserŌĆÖs performances, for instance, interventions that unveil the logic and functions of the artistic field while Fraser enacts its different roles, varying from guide to gallery owner (think of her famous Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk, 1989).2Recontextualising the language of GlauckŌĆÖs speech, publishing, or otherwise presenting it, His MasterŌĆÖs Voice points out how museum structures arenŌĆÖt exempt from corporate lingo and laws. While the institutional critique and ironic twists are precisely apparent in FraserŌĆÖs performances, in CreischerŌĆÖs work it is the textual structure that gives the poem its operative force: line breaks and blanks, the omission of capitals and repetition (ŌĆ£behold behold / we weŌĆØ) give the text as text a rhythm and a drama of its own.

Ilse van Rijn

Poetry as Material Intervention in Contemporary Art

Andrea Fraser, Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk (1989).

In literary terms, CreischerŌĆÖs work is a form of r├®├®criture; a rewrite that, through its very repetition, makes you realize that no two moments are the same, each determined not only by the contexts in which they proliferate, but also by underlining that while letters and words might seem identical, what you want to express with them is not. Or, prior to their expression: language, words, and sentences are a convention, agreed upon and put in place by white, male, heterosexual individuals. Language is an arbitrary code, not equal to the world and displaced in relation to it. Poet Lyn Hejinian calls this displacement a parallax.1Repetition doesnŌĆÖt exist.

Ilse van Rijn

Poetry as Material Intervention in Contemporary Art

Otobang Nkanga, "We Could Be Allies" in First Person Plural: Empathy, Intimacy, Irony, and Rage. Propositions for a Non-Fascist Living #5.

BAK, Utrecht, May 12ŌĆōJuly 22, 2018. Installation View.

His MasterŌĆÖs Voice reads in a radically different way to a work like We Could Be Allies (2017-18) by Otobang Nkanga. Not only are the formal qualities of the poems different, but CreischerŌĆÖs work is staged like a play while NkangaŌĆÖs writing is composed of strictly separated stanzas of similar length. Their respective presentation within the institutional context varies as well:

I could graft myself to you

blend to look like you

hide underneath each layer

So I can be close to you

(ŌĆ”)

If I connect to you

If I am consumed by you

If I crumble with you

Then what do we call us?

what can we become?1

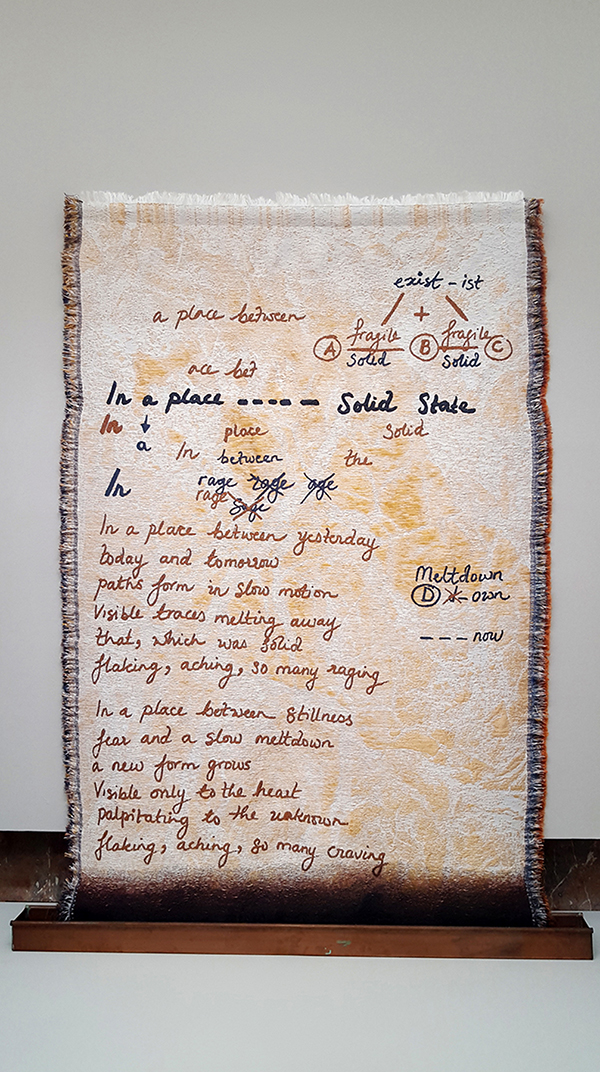

Or witness NkangaŌĆÖs In a Place Yet Unknown (2017). Brown and blue letters and symbols are written in ink on woven fabric. The figures read like a puzzle, or what theorist and artist Johanna Drucker defines as Diagrammatic Writing, the ŌĆ£poetic demonstration of the capacity of format to produce meaning.ŌĆØ2Looked at from a distance, the words, sentences, and strophes transform into abstract, dark forms on a light background. When read, the ŌĆ£meaningŌĆØ of the work transpires due to the placement of the words on the page or, in the words of Drucker again: ŌĆ£The first words placed define the space.ŌĆØ3Notice the punctuation and placement of words and symbols in NkangaŌĆÖs work, always important in writing and in poetry specifically. The visual quality and operative force of these marks is emphasized due to the manifestation of the poem, displayed in a museum context. Something called ŌĆ£meaningŌĆØ is otherwise apprehended once the poem is read aloud, however, the rhythm and sound of the words impose themselves on you in the visual installation, adding yet another dimension to the work. We have already seen that with CreischerŌĆÖs work, the reading is another instantiation of the work. Or, as literary scholar Marjorie Perloff wants it, reflecting on the functioning of poetry in a digital age, a work is differential, it exists in several stages and states, without one version being more authentic than another.4

Ilse van Rijn

Poetry as Material Intervention in Contemporary Art

Otobang Nkanga, In a Place Yet Unknown, 2017.

Woven Fabric, metal reservoir, ink, dye. 266 x 180 cm

HereŌĆÖs a performance by Karl Holmqvist, where youŌĆÖll notice how the reading, given in a very mechanical and monotonous tone, in this case, influences the work. Or rather, the reading is the work, in an unmediated way.

Ilse van Rijn

Poetry as Material Intervention in Contemporary Art

"Numbers," a poem by Karl Holmqvist

"Numbers," a poem by Karl Holmqvist

As these examples illustrate, the materiality of language is diverse, varying from sound to the ŌĆ£heavyŌĆØ meaning quasi-immanent in the words, from ink on paper to the space of the page. And one materiality doesnŌĆÖt exclude the others. Instead of understanding poetry as an enclosed environment, the stanza creating ŌĆ£wallsŌĆØ as a ŌĆ£ŌĆ” pale perimeter for ŌĆ” words to bounce off,ŌĆØ1 to quote Quinn Latimer, I suggest conceiving of poetryŌĆÖs language and words as active, radically open entities that are never at rest. Poetical language explores and exploits this diverging and dynamic capacity of language as always unfolding. Language is movement, either simple or complex.2

It is in this very dynamic capacity that creative subjectivity should be understood, according to F├®lix Guattari. Seizing uponŌĆö

- The sonority of the word, the musical aspect

- Its

materialsignifications with their nuances and variants - Its verbal connections

- Its emotional, intentional and volitional aspects

- The feeling of verbal activity in the active generation of a signifying sound, including motor elements of articulation, gesture, mime; the feeling of a movement in which the whole organism together with the activity and soul of the word are swept along in their concrete unity [author emphasis].3

ŌĆöcreative subjectivities can detach themselves from reigning regimes.4This doesnŌĆÖt imply that poetry is cut off from the world, but that in it the parallax is acknowledged, to use HejinianŌĆÖs term again. Words and world aren't separate and distinct entities. Or, as Guattari formulates it, when you construct meaning in a structuralist vein, attaching the signifier to the signified without further ado, you are subjected to a regime that isnŌĆÖt yours.5

I argue that poetry in the realm of visual art today is conscious of the polyvocality and multiple dimensions, or the breaches immanent in the ŌĆ£single word.ŌĆØ While the language used by Conceptual artists relied upon structuralist and poststructuralist thought, exploiting the duality of language, or the understanding of language conceived as a code, current poetical endeavors in art arenŌĆÖt reducible to either/or. They rather take a position of AND.

To end this essay, I pose the following question: if it isnŌĆÖt scientific meaning that can be gained from poetry, how, then, is knowledge generated by poetry, if at all?

Western cultural tradition is built on the scission between the word of poetry and the word of philosophy, underlines Alain Badiou, among other philosophers.6 Philosophy lacks the means of expression to share its knowledge, while poetry is unconscious but capable of capturing the object through representation. Badiou claims that we live in what he calls the ŌĆ£Age of the Poets.ŌĆØ7In this age the ŌĆ£poem comes to occupy the place where ordinarily the properly philosophical strategies of thought are declared.ŌĆØ ŌĆ£The poetic saying,ŌĆØ consequently, says Badiou, ŌĆ£not only constitutes a form of thought and instructs a truth, but also finds itself constrained to think this thought (emphasis in original).ŌĆØ8 Badiou then refers to the French symbolist poet St├®phane Mallarm├®, who after his great crisis of 1860, declared in a letter to his friend Henri Cazalis, that ŌĆ£his thinking has thought itself.ŌĆØ8Quoting Badiou again: ŌĆ£To think the thought of the poem supposes that the poem itself takes a stance with regard to the question ŌĆśWhat is thinking?ŌĆÖŌĆØ8

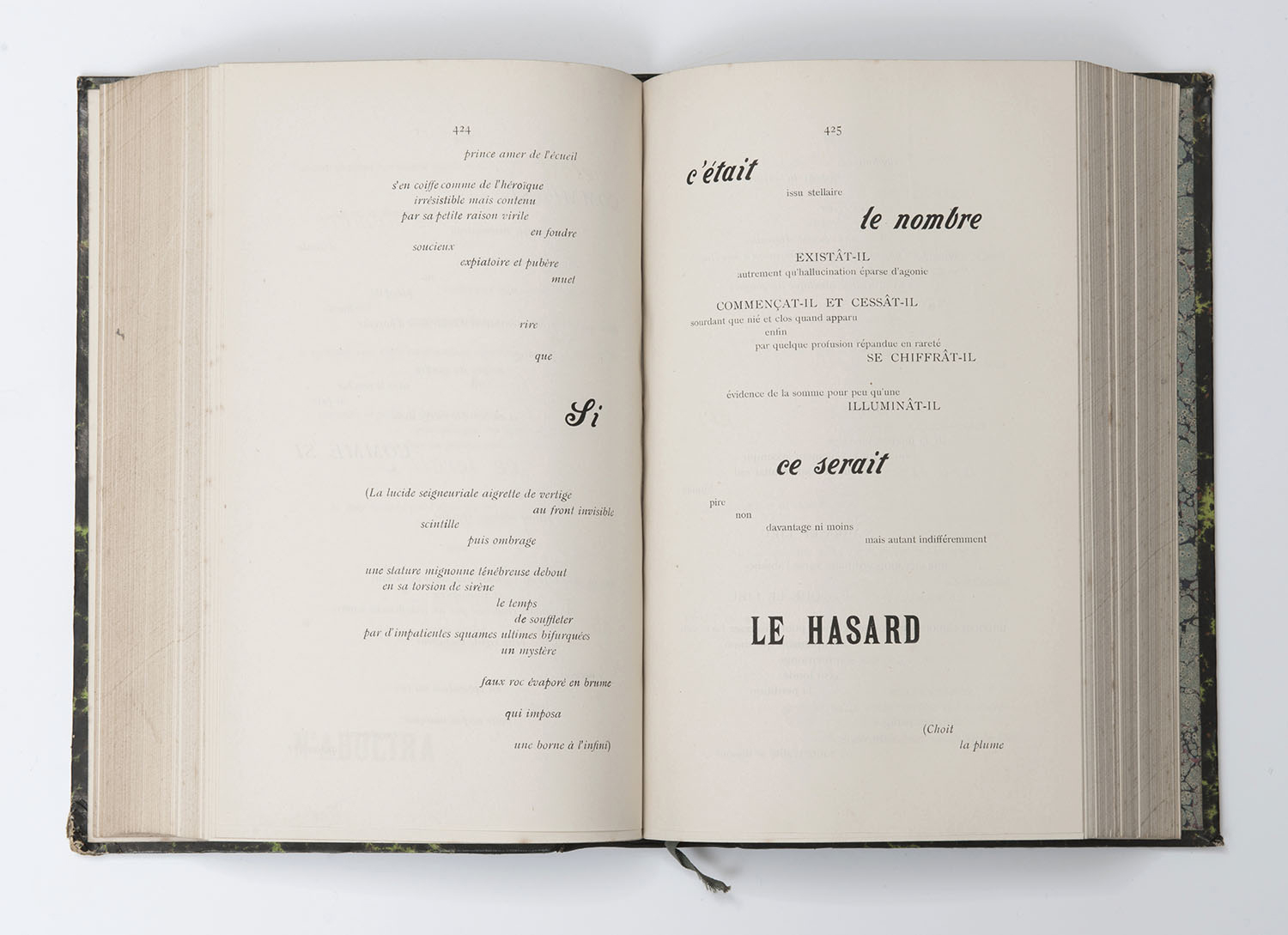

BadiouŌĆÖs is a philosophical enquiry. He concentrates on the conditions for thinking, designating the poem as one such condition. Although his argument bridges the traditional gap between philosophy and poetry, what is left aside, however, is that poetry is more than thinking thought. Mallarm├®ŌĆÖs famous poem Un coup de des jamais nŌĆÖabolira le hazard of 1897 is shaped by the conditions that brought it about: paper and ink, typeface, the format of the book reflecting upon the then emergent newspapers and magazines in which he was published. Mallarm├®ŌĆÖs poem contributed to the enactment of the question of whether the role of language, literature, and poetry could enhance a world that was suddenly flooded with faits divers. The potential of poetry as embodiment and act was further elaborated by Mallarm├® in his lifelong project Le Livre, in which ŌĆ£all that exists in the world ultimately will end up,ŌĆØ9and for which he designed detailed instructions, complete with mathematical formulas, specifying the role appointed to his reader, at what particular moment the page should be turned, for instance, in order for the work to be, literally and theatrically, performed. Beyond thinking thought, and beyond the modernist play of the blanks and the blacks, Mallarm├®ŌĆÖs Le Livre enacted a wor(l)d, breaching the traditional gap between paper, words, and the so-called world in a non-hierarchical way.

Ilse van Rijn

Poetry as Material Intervention in Contemporary Art

St├®phane Mallarm├®, Un coup de d├®s jamais nŌĆÖabolira le hazard, 1897

It is this transversal approach, taking into account the diverging and different domains it crosses, that makes the reading of poetry a challenging and complex activity. You are forced, for instance, to see, to listen to, to experience or sense the polyvocality, the multiple dimensions of NkangaŌĆÖs work. Combined with poetry, her installations suggest a form of intimacy lacking in current networks of production and distribution, and in the means of communication,1including its speed, to which we are accustomed. It acts out a conjunction between irregular, incompatible shapes.2Without directly connecting to systems that surround ŌĆ£us,ŌĆØ you are forced to interpret what remains hidden, silenced and unsaid by these systems. You are urged to ŌĆ£become-other,ŌĆØ in the words of Franco ŌĆ£BifoŌĆØ Berardi, and to change.3

Returning to CreischerŌĆÖs work, the opposite seems to happen here. Appropriating the language of politics and corporate industry, a connection between languages takes place, be it a forced one. Instead of a conjunction asking for interpretation, a juxtaposition is created based on the mechanics of the political, economic interactive machine that already moves ŌĆ£usŌĆØ along. His MasterŌĆÖs Voice taps into the information flows and the empowering connective capacity, ŌĆ£in order to comply with the recombinant technology of the global net.ŌĆØ4The poetical aspect is otherwise revealed, however. Rewritten, recombined, de- and recontextualized, performed, the words read like a parody. The words and sounds turn into a song, a cry. There is a relay between the material phonography and the material substitution. It is in this break that meaning happens. Or, the non-meaning of meaning transcribed as a cry is acted out in the work. According to structuralist thought the cry doesnŌĆÖt have a meaning. For both De Saussure and for Chomsky, speech was ancillary, sound was excluded from their language as science, degraded by accent (De Saussure) or by agrammaticality (Chomsky).5

The cry is the beginning of poetry as song. Poetry as song is an embodied, materialized form of language. The performance of poetry as song and cry upends meaning in more than one way. It not only bridges the gap between language and the world, it also destabilizes coherent, sensical thought, protesting against western concerns that attempted to produce a science of language (structuralism). This doesnŌĆÖt imply that knowledge is absent. The cry of and in poetry is an embodied language of excess that cannot be reduced to categorical thought. The cry, pointing to subjectivation (remember that the first thing you utter as a human being, the sign that you are alive, a living force, is a scream or cry) and considered the beginning of all poetry as song, is banned access to sociality as meaningful exchange, in a hermeneutic, socio-economic, and cultural sense. Or poetry lacks exchange value since it ŌĆ£makes nothing happen.ŌĆØ6As such it disrupts existing orders, infiltrating in reigning regimes. This is the operative force of poetry in the realm of visual art today. Poetry has been used in this disruptive way throughout the ages in fights for recognition of diversity in gender, sex, class, and race. My research pivots around what poetry in the realm of visual art can learn from these traditions. Taking a step beyond, how does it differ and potentially differentiate institutional thought? In its restructuring of language ŌĆ£as we know itŌĆØ poetry offers an alternative to say what cannot be expressed; used in the realm of what is still known as visual art, poetry upends categorical thinking. Advancing justice, especially for historically marginalized communities, poetry is ŌĆ£not a luxuryŌĆØ to borrow the words from poet and activist Audre Lorde. The question remains ŌĆ£how can we use the masterŌĆÖs tools to dismantle the masterŌĆÖs house?ŌĆØ7Poetry in the realm of visual art points to a way.

- Including Tan Lin, Penny Goring, Melissa Broder, Not_I, Ye Mimi and Alex Turgeon. ↩

-

Daniel Penny, ŌĆ£The Irrelevant and the ContemporaryŌĆØ in The New Inquiry (Aug. 2, 2016) see also e-flux, https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/why-is-

poetry-trending-in-contemporary-art/4269 ↩ -

Quinn Latimer, Like a Woman: Essays, Readings, Poems (Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2017). ↩ -

Lyn Hejinian, TheLanguageof Inquiry. (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2000). ↩ - Anne Boyer, A Handbook of Disappointed Fate. (Brooklyn, Ugly Duckling Press, 2018). ↩

-

Marjorie Perloff, Unoriginal Genius:

Poetryby Other Means in the New Century (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2010). ↩ -

Alice Creischer, In the Stomach of the Predators. Writings and Collaborations. ed. Pujan Karambeigi (Vienna: saxpublishers, 2019), 161-66. ↩ -

Joachim Glauck, ŌĆ£http://www.bundespraesident.de/SharedDocs/Reden/EN/JoachimGauck/Reden/2014/140131-Munich-Security-Conference.html

text: Speech to open 50th Munich Security ConferenceŌĆØ (2014) ↩ -

For FraserŌĆÖs writing, that is part and parcel of her artistic work:

Andrea Fraser, Museum Highlights. The Writings ofAndrea Fraser(Cambridge, London: MIT Press, 2005). ↩ -

Like children, we ŌĆ£discover that

wordsare not equal to the world, that a blur of displacement, a type of parallax, exists in the relation between things (events, ideas, objects) and thewordsfor them ŌĆō a displacement producing a gap.ŌĆØLyn Hejinian, ŌĆ£The Rejection of ClosureŌĆØ in TheLanguageof Inquiry (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2000), 48. ↩ -

Otobang Nkanga, ŌĆ£We Could Be Allies (2017-18)ŌĆØ on show at First Person Plural: Empathy, Intimacy, Irony, and Rage. Propositions for a Non-Fascist Living #5 BAK May 12ŌĆōJuly 22, 2018. ↩ -

Johanna Drucker,

Diagrammatic Writing(Eindhoven: Onomatopee, 2013), 1ff. ŌĆ£This is both too obvious to state and so complex that the full exegesis of the act and its implications could take volumes,ŌĆØ Drucker adds (3). Her book pivots around the phrase. ↩ - Ibid., ?? ↩

- Ibid., 103. ↩

-

ŌĆ£

Languageitself is never in a state of rest. Its syntax can be as complex as thought. And the experience of using it, which includes the experience of understanding it, either as speech or as writing, is inevitably activeŌĆō both intellectually and emotionally. The progress of a line or sentence, or a series of lines or sentences, has spatial properties as well as temporal properties. Themeaningof a word in its place derives both from the wordŌĆÖs lateral reach, its contacts with its neighbors in a statement, and from its reach through and out of thetextinto the outer world, the matrix of its contemporary and historical reference. The very idea of reference is spatial: over here is word, over there is thing, at which the word is shooting amiable love-arrows. Getting from the beginning to the end of a statement is simple movement; following the connotative byways is complex or compound movement.ŌĆØ

Lyn Hejinian, ŌĆ£The Rejection of ClosureŌĆØ in TheLanguageof Inquiry (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2000), 50. ↩ -

F├®lix Guattari, Chaosmosis. An Ethico-Esthetic Paradigm, trans. Paul Bains and Julian Pefanis (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995), 14-15. ↩ -

Guattari refers here to the first theoretical essay from 1924 by Mikhail Bakhtin, ŌĆ£Content,

Material, and Form in Verbal ArtŌĆØ in Art and Answerability: Early Philosophical Essays by M.M. Baktin, ed. Michael Holquist and Vadim Liapunov (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990). ↩ -

F├®lix Guattari, ŌĆ£On the Production of SubjectivityŌĆØ in Chaosmosis. An Ethico-Esthetic Paradigm trans. Paul Bains and Julian Pefanis (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995), 1-32. ↩ -

Alain Badiou, The Age of the Poets And Other writings on Twentieth-CenturyPoetryand Prose, ed. and trans. Bruno Bosteels (London and New York: Verso, 2014). See also Giorgio Agamben, The End of the Poem. Studies in Poetics, trans. Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999); Giorgio Agamben, Stanzas: Word and Phantasm in Western Culture, trans. Ronald L Martinez (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 1992). ↩ -

Alain Badiou, ŌĆ£The Age of the PoetsŌĆØ in The Age of the Poets and Other Writings on Twentieth-CenturyPoetryand Prose, 5. ↩ - Ibid., 5. ↩

- ŌĆ£ŌĆ” sommaire veut, que tout, au monde, existe pour aboutir ├Ā un livre,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£Le Livre, instrument spirituel,ŌĆØ in ┼Æuvres Compl├©tes (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1945), 378. ↩

-

ŌĆ£ŌĆ” the poem does not belong to the order of communication. The poem has nothing to communicate. It is only a saying, a declaration, which draws its authority only from itself.ŌĆØ

Alain Badiou, ŌĆ£What Does the Poem Think?ŌĆØ in The Age of the Poets And Other writings on Twentieth-CenturyPoetryand Prose, 23. ↩ - Agamben calls it the ŌĆ£tension and difference ŌĆ” between sound and sense, between the semiotic sphere and the semantic sphere.ŌĆØ Giorgio Agamben, ŌĆ£The End of the PoemŌĆØ in The End of the Poem. Studies in Poetics, 109. ↩

-

Franco ŌĆ£BifoŌĆØ Berardi, The Uprising. On

Poetryand Finance (South Pasadena: Semiotext(e), 2012), 125. ↩ - Ibid., 124. ↩

- Fred Moten, In the Break. The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis and Lodnon: University of Minnesota Press, 2003). ↩

-

ŌĆ£In a memorial poem to Yeats, W.H. Auden wrote ŌĆ£

poetrymakes nothing happen.ŌĆØ Nothing is the realm of uncounted experience.ŌĆØ Emily Roysdon, By Another Name / Uncounted (Amsterdam: If I CanŌĆÖt Dance, I DonŌĆÖt Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution, 2014). See also note 24. ↩ -

Audre Lorde, ŌĆ£

Poetryis Not a LuxuryŌĆØ in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (New York: The Crossing Press and W.W. Norton & Company, Inc, 1993) 36-39. ↩

About the author

Ilse van Rijn is an art historian and art writer working at the crossroads between literature and visual art. Her research is focussed on artists' texts, texts written and produced by visual artists, and questioning artists' writing's textual affinities with feminist critique. She is a lecturer at the University of Amsterdam and the Programme Director of the Temporary Master Approaching Language at The Sandberg Instituut.