Jeroen Boomgaard

The Discourse of Others

For the past one and a half years The Commoners’ Society, a group of ten master students from the Sandberg Instituut, have used visual, digital, and performative tools to propose a new kind of society focused on social interaction and equal opportunities for financial growth and profit. The Commoners’ Society looks for other ways of living, making, owning, sharing, managing, and maintaining; or generally for models of what we call “a new commoning.” In doing so, the group has stumbled upon many questions regarding the potential of art practices in social processes and societal change; questions that are augmented through the hyper-reality we are now confronted with due to the Covid 19 virus. We asked Professor Jeroen Boomgaard to shed light on this urgent but fragile discourse.

—

Commoning is a verb. It is a word that implies a way of doing things together. An act of sharing. Of relating to people, plants, animals, and things according to different rules. Of creating another system. Of moving and resettling, of re-dividing spaces according to new needs. Commoning requires action; it cannot remain just a term. It does not want to be an empty word; it wants results in the form of commons. But it does not imply blind action either. It is based on ideas and ideals that have been formulated and that are debated. These initiate a first act of sharing, which precedes any actual sharing.

Commoning is a verb, and it acts like a verb. It is a word that not only creates the moving and rearranging of relations and occupations, but it also describes or even defines a process, or certain processes. Not everything we do together can be seen as commoning. Having a coffee together does not necessarily start a commons. Certain goods and ways of living are part of commoning, others are not. Sharing a kitchen, and creating other communal spaces is easier than reaching an agreement on how to raise the children. Certain people are included in the plans for the commons, while others remain outside. Their voices are not heard. A specific discourse starts, guides, and controls the coming of the commons. A discourse however that is not so specific that it is isolated from the general discourse used by a society at a certain time and place. Discourse in general usually consists of opposing verbal forces and ways of speaking, for instance, on profit and protest, care and consumption, but all the same it instructs what can and cannot be said, recognized, and accepted. With commoning, the discourse can result in the construction of rules for social control, instructions on what is allowed, and who is not welcome, that close the commons off from its environment and brings the commoning interaction with others to a halt.

Art that wants to contribute in any way to existing commoning projects has to break through this barrier. The shield of norms and regulations that protects the commons must be opened to make space for the heterogeneous, the discourse of the other. But community art—the generic term used for interventions in the public domain based on collaboration with members of a community—is itself often the result of a commoning process. A commoning that unfolds in two different stages. First, in the action of a collective of artists, designers, curators, and organizers working together in and for a specific environment to create a specific event. An action that is, in the same way as described above, preceded and accompanied by a discourse on commoning, on working together. But within this, according to Rudi Laermans, in his very interesting text on artistic commoning, an ambiguity becomes visible that informs any instance of commoning, but that in my view crystallizes in artistic commoning: the desire to co-create collides with the equally strong desire for personal recognition.1 This clash of desires is more explicit in artistic commoning because the intended outcomes are unknown while the personal investment is vast.

The discursive struggles that are part of the artistic collaboration process are of course not separated from the general discourse mentioned above. The artistic discourse, however, occupies its own space within the general discourse—a way of speaking, a use of certain terms—that is more or less common to those within the field of art, but harder to understand for others. This barrier of language stands in the way of the second stage of community commoning that the art project to be wants to attain: the art project has problems in being understood by its potential participants/audiences. The question then is: how can the discursive difference between the unstable construction of ideas, intentions, and words of the art project and the regulative discourse of the commons be connected in such a way that the potential of the commoning process is opened up? The intention of finding other ways to live together unites community art making and commoning but the ideals are formulated in ways that make access and exchange improbable.

We are faced with these questions at the outset of a research project at Zeeburgereiland, Amsterdam titled, Contemporary Commoning: Investigating the Role of Art and Design in Creating Spaces for Public Action. Zeeburgereiland is a newly developed housing area in the East of Amsterdam, that is particularly interesting because of common housing projects already in place or in statu nascendi. In this research, which started on March 1st 2020 and will run for two years, a Postdoctoral researcher from the University of Amsterdam, a researcher from Waag2 , and artists from RAAAF3 on behalf of Rietveld/Sandberg will work together, coordinated by René Boer from Failed Architecture4 and supported by NWO, a Dutch funding organization for scientific research, the property development company BPD Europe and Nautilus, a common housing project realised at Zeeburgereiland. The Casco Art Institute5 will distribute the so-called "recipes" that this research aims to deliver. Recipes that deal with the very same question posed above: how to enable artistic interventions to re-open processes of commoning in order to make new practices of public action/space possible.

Jeroen Boomgaard

The Discourse of Others

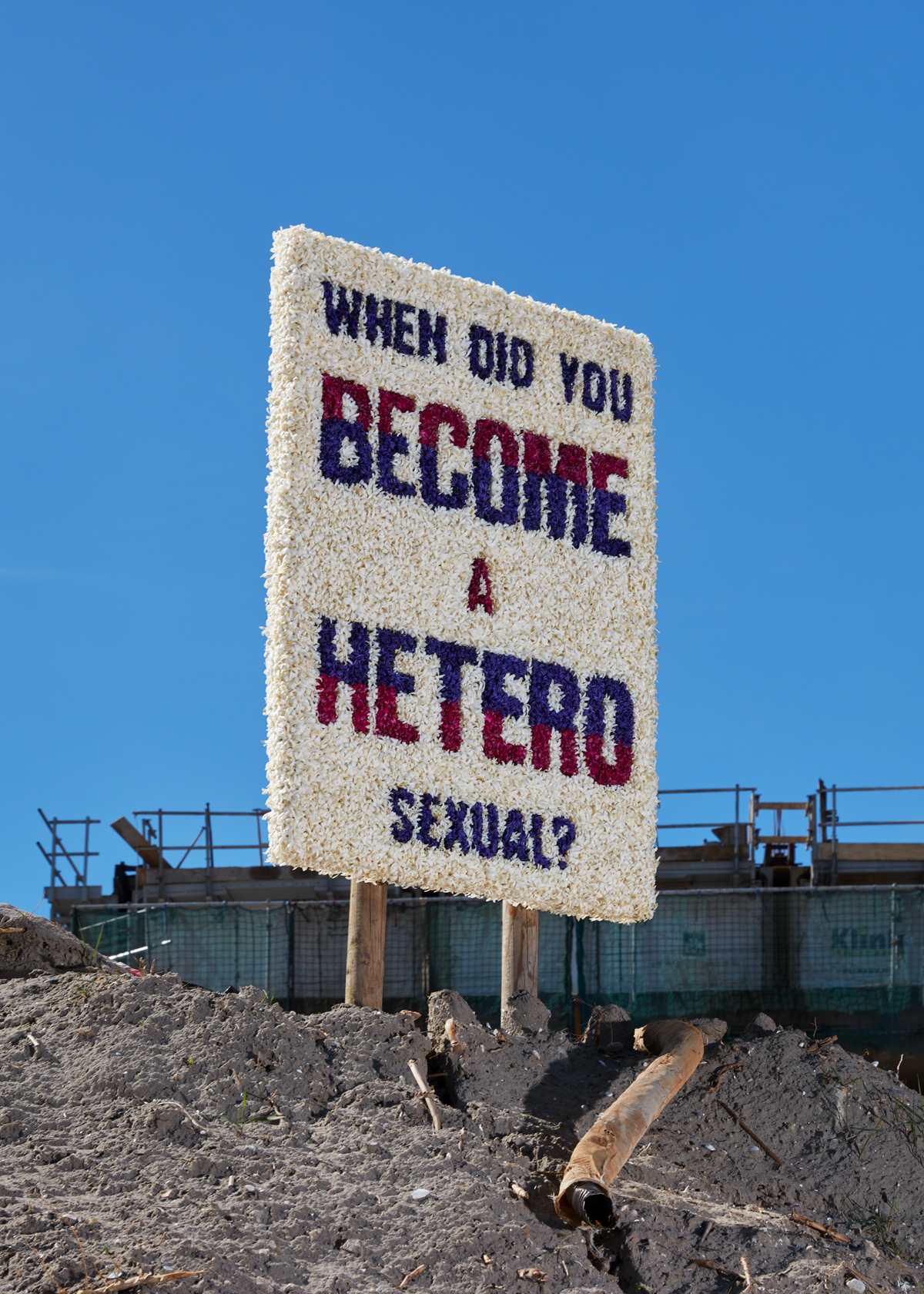

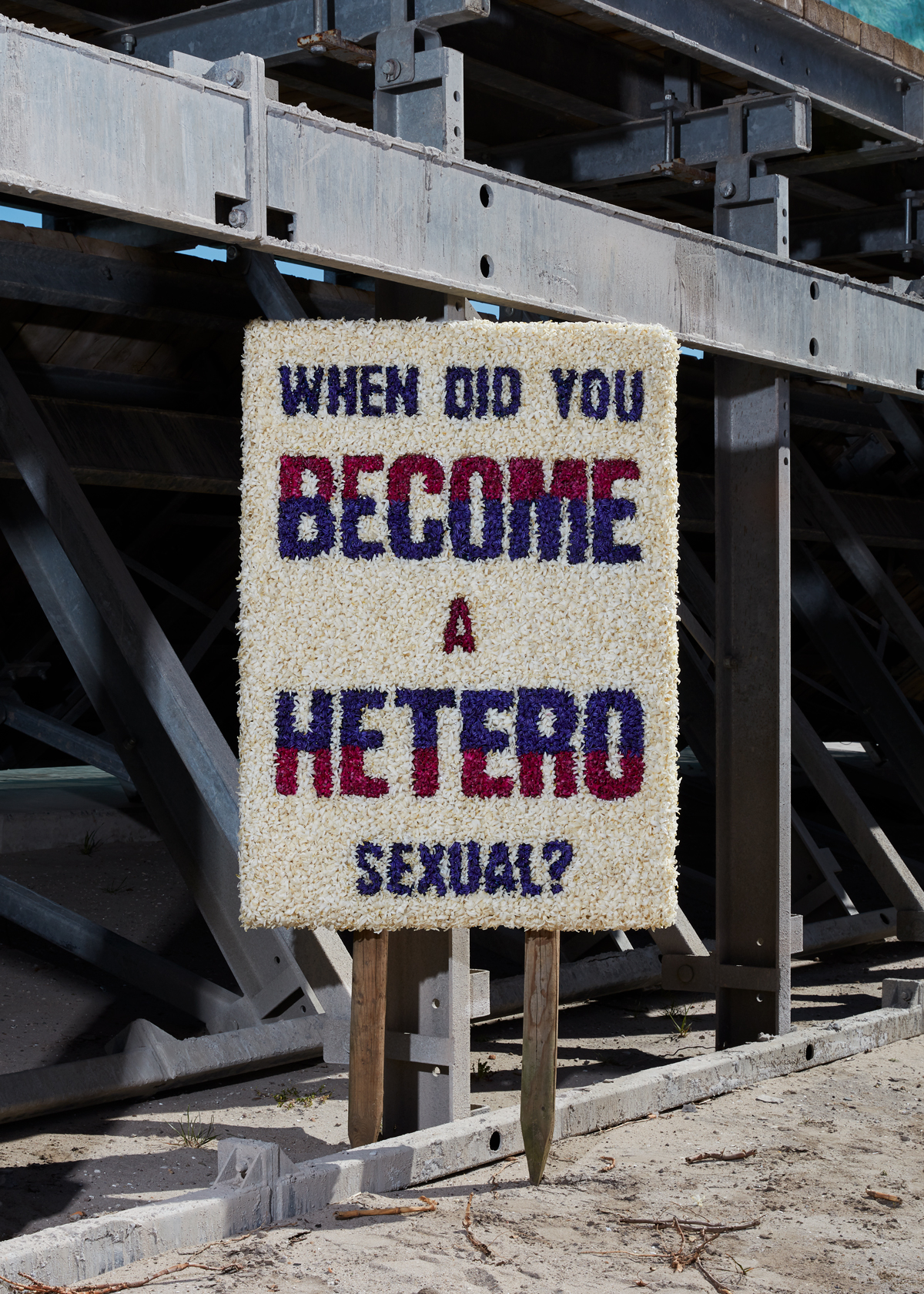

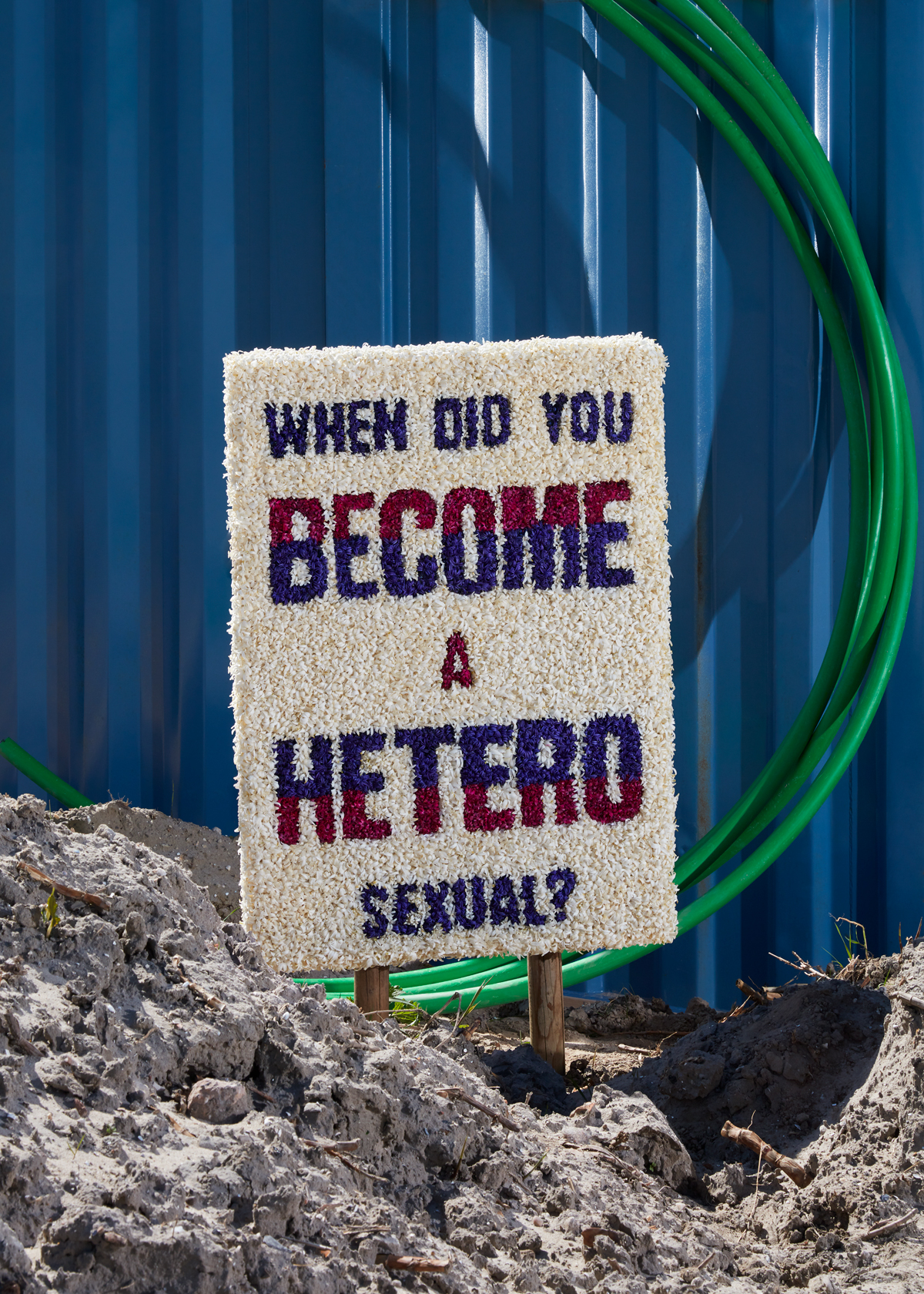

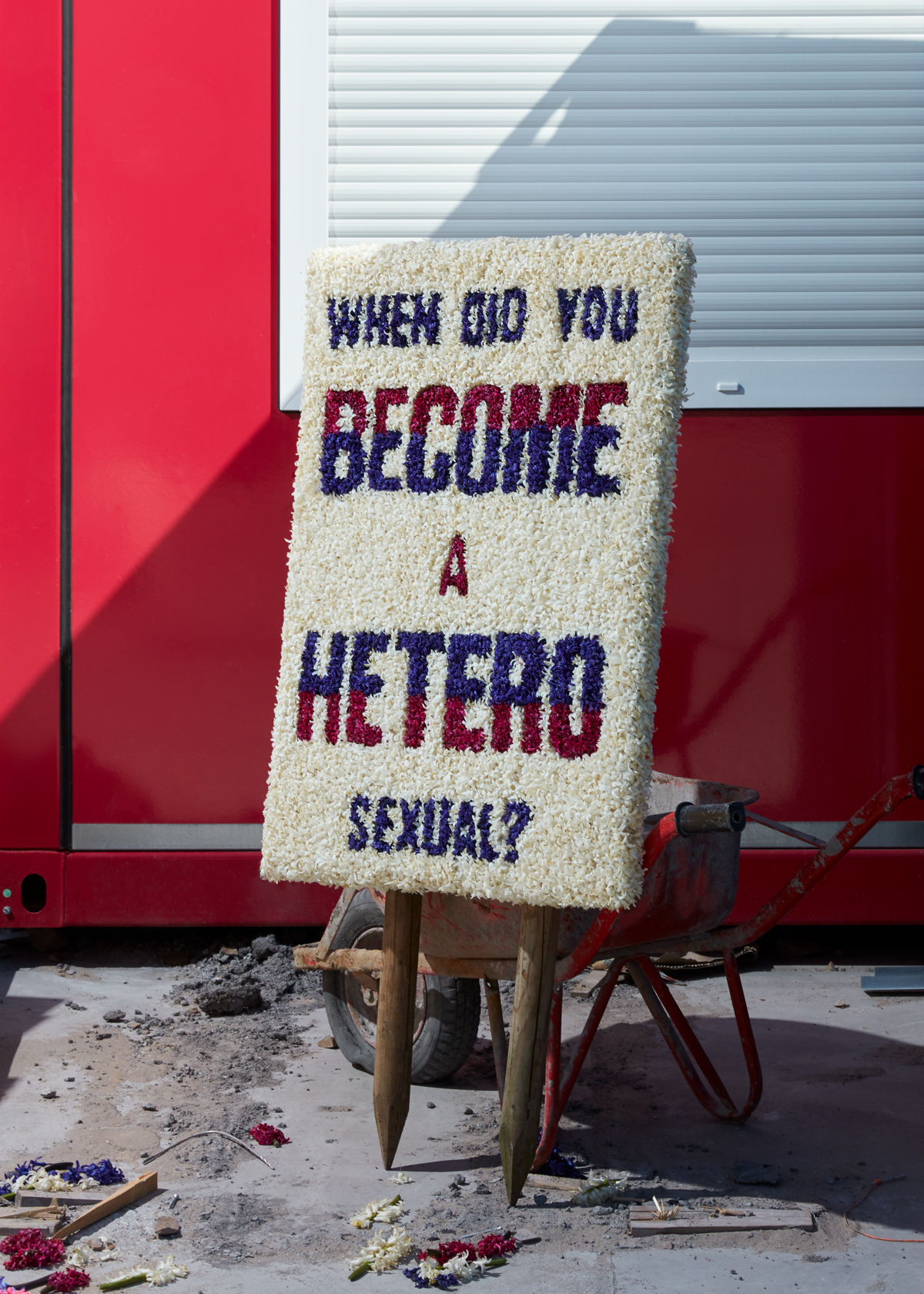

Willem Schenk, Fictional advertising of a neighbourhood queer bar—2020 Zeeburgereiland, Amsterdam.

Flower mosaic, graphic design by Rowena Buur, photography by Lonneke van der Palen.

To understand the possibilities of overcoming the discursive barriers that confront us, it is good to realise that confinement in a discourse is not as strict as it seems. The language we use in relation to shared ideals or ambitions has a tendency to reduce them to acceptable ideas, especially when used as a tool for instruction and communication. But the door of this language prison is not locked. Words can find new combinations with other words, concepts can shift to another terrain and regain power by doing so. To grasp the influence, or lack thereof, of discourse on our daily thinking and doing it is useful to compare it to the force of architecture on our bodies and behaviour. Architecture is the place where ideals solidify into form. With the best intentions, progressive ideas about new forms of living together and of structuring society are designed to be built in immobile constructions we call architecture that, by making the ideals present, rob them of their future potential. In the Contemporary Commoning project we look back at the models for living better lives as implicated for instance by the theories and buildings of the Amsterdam School or of the International Modernist Movement that resulted in the construction of the Bijlmer. While making earlier ideas of commons and commoning real, these buildings also condition states of conformity for those who live in them and nudge people into normalization. But as convincing and coercing as these buildings might be, they still carry, as Walter Benjamin would have it, the spark of the original ideal, from before they were built into failure.1 In spite of their overpowering presence, the people living in them, will always “misunderstand” them, and use them in a contrary way.

In a society in which the discourse is fragmented and contradictory, and the forms of culture are diverse in terms of style and taste, gaps and holes in the built environment are present, making unforeseen futures possible. So why not go ahead and let art intervene in the words and the spaces of commoning? Discourse may not be all pervasive, but it is still very cunning. And one of its main tricks, with regards to the arts, is that it provides and regulates a special section of the general discourse as art speak, while simultaneously announcing or denouncing this section as ART, a seal that qualifies and disqualifies at the same time, and that in general indicates a separate field, hard to enter into and even harder to handle. This sign of separation stands in the way of art projects that have the ambition to directly intervene in society. Following Jacques Rancière, it is also the precondition for any successful intervention at all. An aesthetic effect is, according to him, initially an effect of dis-identification.2 A break with accepted ways of seeing and saying is necessary for a new distribution of the sensible to appear.

Although convinced of the political potential of this aesthetic dis-identification, Rancière all the same warns against setting ones hopes too high. According to him, the dis-identifying effect cannot be calculated.3And that is logical: if the discourses, spaces, and images that regulate our daily life are not able to keep complete control, if dis-identification is a possible effect, then dis-identification in its turn cannot be expected to have a direct and definite impact. Or, in this specific case, does artistic intervention on Zeeburgereiland have any chance of creating spaces for public action when the intervention is either inaccessible because of its label ART, or is simply a wild guess without consequence?

If this is the conclusion we might as well stop the research project at its very beginning. There are, however, aspects to this enterprise that give reason to believe the prospects are not as bleak as all this. First of all, the project is located in the public domain of Zeeburgereiland, a space defined by all kinds of practices, that is not and cannot be owned by anyone in particular, although under constant threat of privatizing impulses and data control. If public space is the terrain where the commons and the artists come together, or collide, both sides are on unstable territory Outside of its designated spaces art is no longer just ART; and beyond the walls of the common housing, the rules of inclusion and exclusion that define the commons make no sense. As art disjuncts from what we know, but also conjuncts existing elements, the connection from the art project to the commoning process is possible. The connection is situated in the shared longing for other ways of living, in the common utopian core that underlies commoning from the past to the present, and in the desire to connect itself. The condition for this connection to happen is starting a discourse of sharing without any intended outcome. A sharing of ideas, words, forms, and actions that do not wish to communicate anything but that simply make present. The dis-identification resulting from this works on all involved: the commoners no longer identify exclusively with their common project, the artists no longer identifying exclusively with art. They meet in dis-identification and this makes it possible for the commoning to start all over again.

Bibliography

Gielen, Pascal. “Common Aesthetics. The Shape of a New Meta-Ideology.” In Commonism. A New Aesthetics of the Real. Edited by Gielen, Pascal and Dock, 75–87. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Valiz, 2018.

Laermans, Rudi. “Notes on Artistic Commoning.” In Commonism. A New Aesthetics of the Real. Edited by Gielen, Pascal and Dock, 135–47. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Valiz, 2018.

Rancière, Jacques. The Emancipated Spectator. London: Verso, 2009.

Stavrides, Stavros. Towards the City of Thresholds. New York: Common Notions, 2019.

Stavros Stavrides, “The Potentials of Space Commoning.” In Commonism. A New Aesthetics of the Real. Edited by Gielen, Pascal and Dock, 345-363. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Valiz, 2018.

-

Rudi Laermans, “Notes on ArtisticCommoning” in Commonism. A New Aesthetics of the Real, eds. Gielen, Pascal and Dock (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Valiz, 2018), 141. ↩ - Waag, Technology & Society: https://waag.org/nl/home ↩

-

RAAAF (Rietveld–

Architecture–Art-Affordances): https://www.raaaf.nl/nl/ ↩ - https://failedarchitecture.com ↩

- Casco Art Institute: Working fort he Commonsis an institution-in-practice for producing, studying, and situating art to work for the commons: https://casco.art/ ↩

-

This is the foundation of Benjamin’s historical research as compiled in his work on Paris in the 19th Century:

Walter Benjamin, Das Passagen-Werk (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1982) ↩ -

Jacques Rancière, “Aesthetic Separation, Aesthetic Community” In The Emancipated Spectator (London: Verso, 2009), 73. ↩ -

Jacques Rancière, “Aesthetic Separation, Aesthetic Community”, 75. ↩

About the author

Jeroen Boomgaard is an art historian and art critic. He is currently Professor of Art and Public Space at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie and head of Master Artistic Research at the Universiteit van Amsterdam, both in Amsterdam. Boomgaard also directs the research group Art & Public Space (Lectoraat Kunst en Publieke Ruimte), a partnership between the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, the Sandberg Instituut, the Universiteit van Amsterdam, and the Virtueel Museum Zuidas (or VMZ), which stimulates research and theoretical reflection on the role of art and design in the public domain. He regularly writes articles about art and public space for publications such as Open. Cahier on Art and the Public Domain. In 2008 he edited a collection of essays on art in public space, High Rise – Common Ground, Art and the Amsterdam Zuidas Area. He also co-edited (with Bart Rutten) the book The Magnetic Era: Video Art in the Netherlands 1970–1985 (2003). Boomgaard lives and works in Amsterdam.Â