Gabrielle Kennedy

Cut-Up for Truth | How collage dominates culture from Basquiat to Sandberg

Since its inauguration as a radical technique fifty years ago, cut-up, or collage has continued to dominate the global cultural landscape. This winter the line outside the Jean-Michel Basquiat retrospective at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris took over an hour (even with pre-ordered tickets).

Throughout the 1980s, Basquiat was a master at cut-up, collage, re-mix and sampling. As a literary technique, cut-up can be traced back to the Dadaists in the 1920s, then popularized in the late 50s and 60s by the poet William S. Burroughs. Since then it has been disseminated across all genres from literature to film, photography, music, as a more inclusive way to honor inspiration and even understand culture.

Back in 2007 critic and writer Jan Verwoert penned a poignant essay titled Living with Ghosts: From Appropriation to Invocation in Contemporary Art. ãArtists appropriate when they adopt imagery, concepts and ways of making art other artists have used at other times,ã he wrote. ã[They do this] to adapt these artistic means to their own interests, or when they take objects, images or practices from popular (or foreign) cultures and restage them within the context of their work to either enrich or erode conventional definitions of what an artwork can be.ã1

It took some nous for Post-modernism to muscle a position away from its Modernist predecessors and be accepted in mainstream discourse. Originality, the Post-modernists argued, is a scam, a gross ideological untruth designed to bolster the genius of the artist. ã[Post-modernists] position art production as the gradual re-shuffling of a basic set of cultural terms through their strategic re-use and eventual transformation,ã wrote Verwoert. 2

So while contemporary discussion has been ripping white privilege, the patriarchy and the limitations of binary thinking out of university tutorials and into prime time news coverage, cut-upãs role in culture has been evolving live-stream. More than a mere technique, cut-up thinking is challenging the connect between art and the society it reflects; it is obliging artists to take more responsibility for the unanticipated effects their referencing and borrowing can have on others. It is a mindset that unravels creative inspiration down to its tangible elements that each demand proper attention.

Post-modernism is no more a rarefied or only academic pursuit. Today cut-up is culture; a way of understanding the networked nature of a shared cultural condition. It seems fitting, then, that the Sandberg Instituut took on the technique as a topic for its Temporary Program, Radical Cut-Up. Headed by Berlin-based curator, writer and artist Lukas Feireiss, Radical Cut-Up is a two-year Master program that encourages its participants to ãcopyã albeit with proper methodology, leading to an informed position. Throughout the course students rethink the very act of cultural production.

In The Ecstasy of Influence, Jonathan Lethemãs says: ãEvery idea, every creation, is a combined effort of everything we've ever witnessed and experienced. We should no longer regard the artwork as an end point, but as a simple moment in an infinite network of contributions, refuse any form of ãsource-hypocrisyã and boldly accept all ideas as second-hand, consciously and unconsciously drawn from a million outside sources.ã3

In positioning the course Feireiss embraces this while focusing on the colossal impact new digital technologies have had on the production and circulation of images, text, sound, and objects. He himself defines cut-up as ãa mixture or fusion of disparate elements, or the art of carefully crafted juxtaposition ãÎ the mixing and reconfiguration of existing materials to produce new outcomes.ã

ãBut I donãt really agree with Feireiss on any of this,ã says course student and new media artist Daan Couzijn. Itãs a particular Sandberg traitãfor students to remain stridently vocal on the content, vision and even purpose of a course.

ãI donãt even like the word collage,ã Couzijn continues. ãIt is not triggering to me. Nor is it about mixing up themes and materials. To me it is really about a deeper understanding of authenticity.ã

The idea that authenticity doesnãt exist, and maybe never has, has been philosophized by everyone from Rousseau to Heidegger (it would be inauthentic for me to look up and rehash their positions here). More simply and less wordy, ãBoom for Realã was Basquiatãs catchphrase for anything he deemed authentic back in a time when Hip-Hop and the Post-Punk rock scene were emerging as big influencers in Manhattan. Sampling from high and low culture, politics, sport, and graffiti offered a new direction and a big hope to a generation of kids wanting to avoid the malaise of cynicism in favour of something that felt more active, even hopeful.

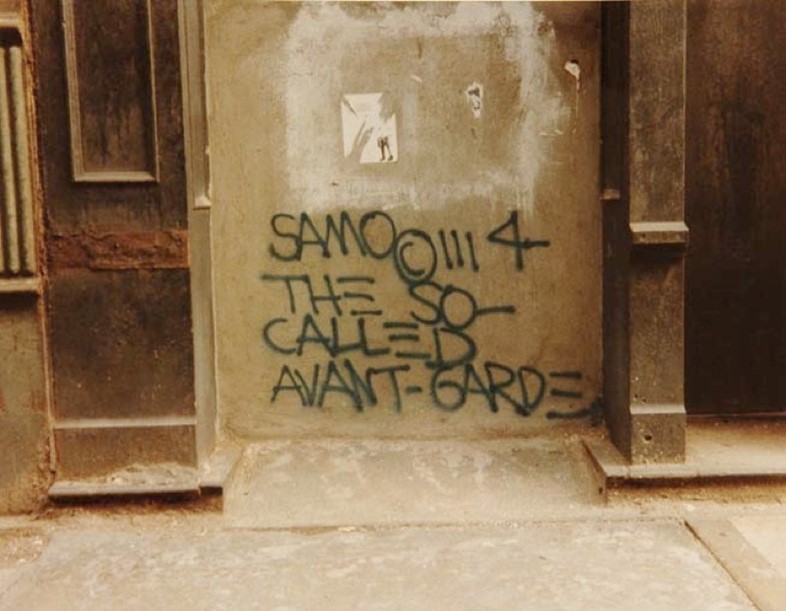

ãBasquiat really is a major influence on a lot of us in Radical Cut-Up,ã says Javier Rodriguez, a Spanish graphic designer. ãTo me he was strongest in his SAMOôˋ stage. It was amazing, a real street movement.ã

Gabrielle Kennedy

Cut-Up for Truth | How collage dominates culture from Basquiat to Sandberg

SAMOôˋ The so-called avant-garde

SAMOôˋ was a play on the phrase ãsame old shitã and was the tag Basquiat used to sign off the sarcastic, social and political comments he was scrawling across walls in lower Manhattan.

ãSAMOôˋ as an alternative 2 playing art with the ãradical chicã sect on Daddyãs $ funds.ã

ãSAMOôˋ as an escape clause.ã

ãSAMOôˋ as an end to mindwash religion, nowhere politics and bogus philosophy.ã

Gabrielle Kennedy

Cut-Up for Truth | How collage dominates culture from Basquiat to Sandberg

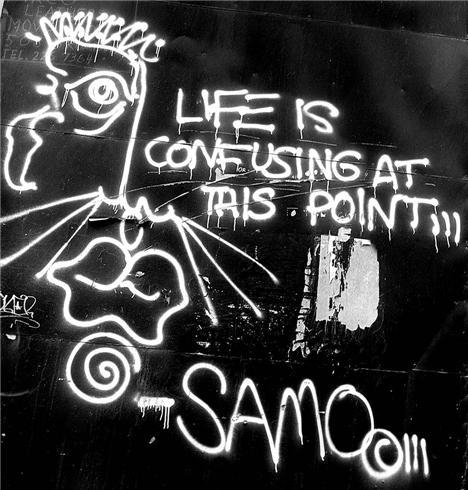

SAMOôˋ Life is confusing at this point

But cut-up has come a long way. While Basquiat might have been using it as a tool to mock bogusness, Sandberg students use it to mock, but also reflect on themselves and the contemporary, self-defined artist.

The Radical Cut-Up course is informally an extension of two previous Temporary Programs that focused on materialsãMaterial Utopias and Materialisation in Art and Design. Awkwardly, but also interestingly, Radical Cut-Up seems to have attracted students focused on materials, but also a group who applied with a fascination for the politics and potential of cut-up. I say potential because the world or at least our understanding of it has changed. No more is the cultural environment defined by steady or linear progress, but rather by a ããÎ multitude of competing and overlapping temporalities born from the local conflicts that the unresolved predicaments of the modern regimes of power still produce. The political space of the globe is mapped on a surreal texture of criss-crossing time-lines,ã wrote Verwoert. 1

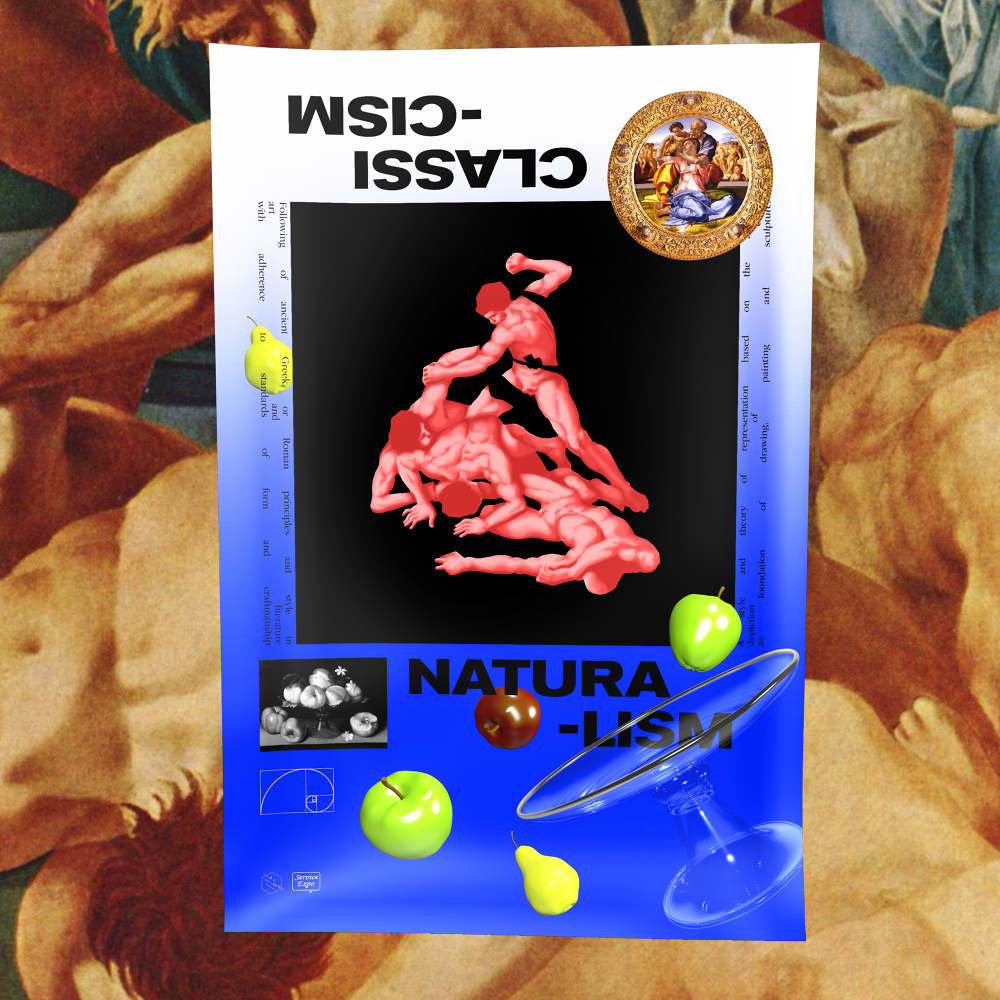

Rodriguez, for example, chose the course to further explore and close the gap between art and design. ãTo me the difference is non existent,ã he says. ãIt is just that artists like to create a hierarchy with themselves at the top. ãI think conceptually. I do art and design. I make books and posters. To me it is all the same.ã

Again Basquiat becomes relevant. ãThe jump from workshop to street-art to gallery is really important,ã Rodriguez continues. ãArt can land anywhere, not just in a white cube gallery where you can too easily get stuck with your own ideas. That can be really boring. I like how in design there is a commission, a budget and restrictions that you have to work creatively with. It is an approach that helps you to not get complaisant with your way of thinking.ã

And for Argentinian artist Augustina Woodgate, who has been working on various incarnations of a mobile radio station, collage is more about infrastructure than materials. ãI like to look at spaces and explore the way infrastructure shapes it,ã she explains. It is also how she is approaching her time at Sandberg. ãI never intended to stay in one department,ã she says, and only a school like Sandberg would have allowed this. With the blessing of course director Feireiss, I move around. I cut and paste according to my needs. I am interdisciplinary. I donãt stick to art or science. I don't want to be defined. I like to bring worlds together.ã

And like Basquiat, Woodgate takes her ideas to the street. ãI donãt exist in a radio station,ã she says. ãI am mobile. I take the city to events and to real life. In that way I am interested in connections and distribution mechanisms. To me art is about intentions and proposals and I see Sandberg like thatãa proposal for a different kind of education.ã

Gabrielle Kennedy

Cut-Up for Truth | How collage dominates culture from Basquiat to Sandberg

Augustina Woodgate, Autopiloto at New Terrains, Silicon Valley, CA (2018)

Theory is a major component in the first year of Radical Cut-Up with tutors from diverse backgrounds providing reading lists and initiating discussions. The aim is to guide students towards a better critical (self)understanding and engagement with the ethics and responsibilities of appropriation and (re-)use. ãIt was interesting,ã says British illustrator Adam Bletchly, ãbut for me theory can become a bit wishy-washy so I preferred it when we jumped from theory to talks about what is happening in the real world. Then the classes became more socially relevant.ã

Which is exactly what the cultural environment needs nowãmore self-awareness amongst artists and designers with better skills to critically analyse their own work, especially with an intersectional dimension. This means more accountability not just for copying and combining, but also a fundamental rethink of the decisions made in the processãthe ethics, politics and economics of cut-up.

A unanimous agreement by all Radical Cut-Up studentsãmaterially or politically drivenãis on the subject of cultural appropriation which they have been questioning with regards to property, ownership, use and sharing.

Iãll dodge the wishy-washy and quote how writer Jonathan Heaf referred to cultural appropriation in last monthãs GQ Magazine. ãTrigger warning: cultural appropriation isnãt about fashion or music or morality or about scoring points on social media, and if you think it is youãre probably a pale, sickly millennial. No, cultural appropriation is about being utterly ignorantãignorant of a minority cultureãs journey and historical suffering.ã 1

In his essay Verwoert referred to this as commodity culture saying:

ã ãÎ it should be possible to cut a slice out of the substance of this

commoditycultureto expose the structures that shape it in all their layers. It is also the hope that this cut might, at least partially, free that slice of materialculturefrom the grip of its dominant logic and put it at the disposal of a different use. The practical question is then where the cut must be applied on the body ofcommoditycultureand how deep it must go to carve out a chunk of material that, like a good sample, shows the different temporalities that overlie each other like strata in the thick skin of thecommodityãs surface. The object of appropriation in this sense must today be made to speak not only of its place within the structural order of the present materialculture, but also of the different times it inhabits and the different historical vectors that cross it.ã2

Basquiat might be chuckling. His art fought power structures and racism, confronted gentrification before it became an it topic, and sneered at cultural appropriation and the commodification of the hipster. His art was self-awareness.

ãThe thing about Basquiat that I find really relevant to my own work is that nothing is accidental,ã says Bletchly. ãAll his elements, and all his arrangements are there for a reason. Nothing is just for the sake of it ... and you can break it all down and then theorize on every feature. This is similar to how I work.ã

ãBut when it comes to controversial topics like cultural appropriation in the art world there is no right or wrong answer,ã continues Bletchly. ãAll I know for sure is that exposing sources is really important. Too much is purposely hidden or blindly ripped off, with no honesty about inspiration. Too many artists play with their cards close to their chests and then when they get found out, they look bad. But people need to stay calm and just admit that nothing is as original as its been made out to be, and maybe by disclosing this, a new type of originality will be borne.ã

Gabrielle Kennedy

Cut-Up for Truth | How collage dominates culture from Basquiat to Sandberg

Poster produced for NRMAL festival in Mexico City by Adam Bletchly.

ãFor me itãs more about knowing where your subconscious comes from,ã says Couzijn, ãunderstanding the root of your inspiration, which can sometimes be problematic, especially if you have not considered its core.ã

ãIãve also learnt to really question my imagery,ã says Rodriguez. ãWhere the colors and symbols come from and how they have been used before matters more than I ever realized.ã

ãYea, but it is also important to point out that we are all just figuring this out,ã admits Couzijn. ãI am not always sure how to deal with what I discover in the process, or how to translate and communicate my results. That is where it can go wrong. Itãs a really complex subject and the course doesnãt pretend to have all the answers.ã

Whichãnot coincidentallyãwas the very point always feted by Basquiat. The revealing of deep-seated conflicts, the combination of disparate elements, the recognition of the creative power of opposing forces.

For his final first year assessment Bletchly created a tapestry based on 15th and 16th century woodcuts, which he scanned, re-drew and re-portrayed. In his assessment he talked about each element separately explaining why it was included.

Rodriguez collaborated on a monumental canvas with fellow student and French artist Lou Buche, where a back-and-forth of four hands created spontaneous and colorful improvisations.

Gabrielle Kennedy

Cut-Up for Truth | How collage dominates culture from Basquiat to Sandberg

Javier Rodriguez Fernandez and Lou Buche (2018)

Couzijn made a film of a fat man dancing. ãAnd a girl in my class asked me why I hadn't chosen a person of color, and was that a conscious decision?ã he says. ãIt was a difficult question because the skin color can change the narrative. I felt conflicted. Right now I donãt know how to navigate my way through these sorts of issues, but I know for sure it is good to talk about it. In the theory classes we really came to better understand that the question is not whether we are racist or not, we all are. It is embedded in our thinking. The question should be are we intentionally racist yes or no? Then you donãt have to be PC, you just need to stay open to the truth that you might say or do something that is racist, own up to it, and try to change it. That is your responsibility.ã

Gabrielle Kennedy

Cut-Up for Truth | How collage dominates culture from Basquiat to Sandberg

Daan Couzijn, Fat Man Dancing (2018)

It is alsoãcategoricallyãthe responsibility of art education. ãFor me this Radical Cut-Up Sandberg Masters is not about getting a job, but about personal gain,ã says Rodriguez. ãI am a designer and after I graduate I will still be a designer, only Iãll do it better ãÎ at Sandberg we have learnt how to stay independent, small and collaborative. How to take the opportunities afforded by the unusual position design holds in the Netherlands and make it work elsewhere.ã

Which is exactly the point Feiressã wants his graduates to imbibeãthe urgency of upholding a healthy distrust of any single narrative, in favour of the Post-modern realization that any pursuit of truth necessitates a multiplicity of perspectives and contradictions. As he puts it himself: ãIf anything, Radical Cut-Upãs aim is to explore new possibilities of artistic storytelling that cultivate a heightened sense of contemporary cultural reflexivity.ã

- Verwoert, Jan. "Living with Ghosts: From Appropriation to Invocation in Contemporary Art" in Art & Research, Vol.1. No.2, Summer 2007, 1. ↩

- Ibid. 1 ↩

- Lethem, Jonathan. "The Ecstasy of Influence: A Plagarism" in Harper's Magazine, February 2007. https://harpers.org/archive/2007/02/the-ecstasy-of-influence/ ↩

- Verwoert, Jan. "Living with Ghosts: From Appropriation to Invocation in Contemporary Art" in Art & Research, Vol.1 No.2, Summer 2007, 3. ↩

- Heaf, Jonathan. "Cultural appropriation is about being utterly ignorant" in GQ Magazine, 13 October 2018. https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/what-is-cultural-appropriation ↩

About the author

Gabrielle Kennedy is an Amsterdam-based design journalist and editor. From 2009 to 2014 she was editor-in-chief of Design.nl, and from 2014 to 2017 was the in-house journalist at Design Academy Eindhoven. She has written about design for The Australian, The Japan Times, Singapore Straits Times, The Economist, POL Oxygen, Dezeen, Wallpaper, and Icon Magazine among others.