Jules van den Langenberg

Germfree Adolescents

Germfree Adolecents by X-ray Spex

I know you're antiseptic,

your deodorant smells nice

I'd like to get to know you,

you're deep frozen like the ice

There is a thin line between cultural appropriation and inspiration. After sitting on Andy Warhol’s face for a few months I started to have mixed feelings. The backside of a matching denim jacket and jeans depicts three screen printed self portraits of the artist in a photo strip, an outfit that is one outcome of the appointment of Belgian designer and art collector Raf Simons as the Chief Creative Officer for fashion brand Calvin Klein in 2017.

Jules van den Langenberg

Germfree Adolescents

Calvin Klein denims and trucker jacket with Andy Warhol portrait.

In this role, Simons, who gained fame early in his career for an aesthetic that drew on sub cultures like New Wave and Punk, was responsible for overseeing the creative side of the business for Calvin Klein, from the runway to mass marketing campaigns. For Simons, this meant intervening in the rather mainstream image of a brand peddling American heritage, and tying the ready-to-wear and more experimental runway collections together where before these were separate outlets.

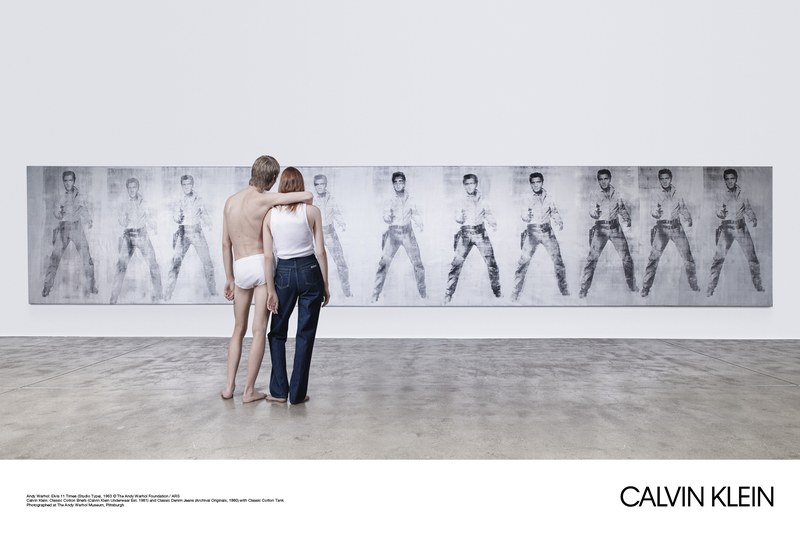

The apparel company managing Calvin Klein, PVH, described the start of this commercial collaboration as “embarking on a brand journey to capture cultural moments and communicate with consumers through more of an artistic lens.”1 This statement launched the spring 2017 advertising campaign featuring models in underwear bearing the rebranded CK logo, standing in front of works by artists Dan Flavin, Richard Prince, Sterling Ruby and Andy Warhol, situated in white cube gallery and museum spaces. The campaign set the tone and gained mass media attention. In just two years, Calvin Klein and Raf Simons set up new retail environments—dubbed by Ruby Sterling as total-room artwork installations—secured a license from the Andy Warhol Foundation to print material form the Pop Art archives, and held an exhibition of Warhol's screen print series Shadows at the Calvin Klein head quarters in New York in collaboration with DIA: Beacon.2

Jules van den Langenberg

Germfree Adolescents

Calvin Klein ad campaign with Ruby Sterling's Flag (4791).

He's a germ free adolescent,

cleanliness is her obsession

Cleans her teeth ten times a day

Scrub away, scrub away,

scrub away the S.R. way

The methodology of a creative director or curator delving into cultural heritage and archives has become a recurring strategy, both for exhibition making in museums and the repositioning of corporate brands. Arts and heritage institutions eagerly seeking governmental and private funding continually delve into the past to resurrect national icons, be they artists, architects or designers. The fashion industry explicitly situates the archive of a brand and future trends in continuous dialogue, recycling the past in the present and passing off what comes down the catwalk as new. In what is now recognised as a period of growing right wing conservatism and attempts at the hygienisation of society, heritage is a trump card used to mobilise communities in deciding who belongs and who doesn’t. Heritage, in short, is used to gain popular support, across art, fashion and politics.

In 2018, Warhol’s self portrait ends up printed on a pair of Calvin Klein jeans, a gesture he might have appreciated. This comes at a time when cultural institutions and museums are rewarded for being more public and inclusive. It is possible that some Calvin Klein consumers liked the look of the photo strip on their denims without knowing the history behind the image, but that doesn't negate the potential reach of Simons' effort. Museums and cultural institutions can only envy the agility and spread of a Calvin Klein campaign in disseminating iconic images from the archive of recent art history.

The pace at which the fashion industry releases new collections with mid season capsules and late season drops is in uncanny correspondence with the ideology of Andy Warhol’s late work. As first a creative director, and second an artist—or working to collapse the distinction between the two—Warhol focussed on a society characterised by fifteen minutes of fame. Ushering in the era of social mediasocial hierarchiessocial mediafame.

You may get to touch her

if your gloves are sterilised

Rinse your mouth with Listerine,

blow disinfectant in her eyes

The cultural appraisal by the creative industry and its critics, as well as the various fashion awards that followed Simons’ work at Calvin Klein, were paralleled by a decrease in sales by the traditional consumers of the American brand—the so called mass market. This drop in sale figures led to Calvin Klein and Simons parting ways after less than two years, causing yet another short spike in attention from the fashion media. PVH’s Chief Executive Officer, Emanuel Chirico, issued a statement during a stakeholders meeting saying that the collaboration had become “too elevated and too fashion-forward for our core consumer.”1 This outcome is an example of the difficulties that go along with attempts to commodify culture and heritage for a mass audience, raising questions about how artistic thinking and economics relate.

He's a germ free adolescent,

cleanliness is her obsession

Cleans her teeth ten times a day

Scrub away, scrub away,

scrub away the S.R. way

One way to interpret Warhol’s work was that he did not differentiate people by virtue of their status. Emulating the strategies of mass media, he printed, published and distributed portraits of Mao just as easily as Marilyn Monroe or the nameless victims of a car crash.2 Warhol's intention was to use mass production techniques to place his art on an equal footing with consumer objects. In some cases, as with the famous Brillo Box, his work doubled as a consumer object. Let’s assume Simons’ effort at Calvin Klein had similar motives to the Warholian notion of commodifying art to defy a society of exclusivity and positioning art in the realm of the consumer. Could these strategies on the part of Warhol, and subsequently echoed in Simons' work with Calvin Klein, be seen as an act of commoning—reducing high art to the level of a commodity, outside of the gallery or museum and distributing it for the common good

Jules van den Langenberg

Germfree Adolescents

Installation view of Andy Warhol's Shadows series at the Calvin Klein Headquaters, organised in collaboration with DIA: Beacon.

To answer this question first requires an understanding of what it means to common at a moment when commoning is becoming increasingly pervasive in artistic discourse, both as a theoretical framework and as a course of action. As opposed to appropriating, and beyond simply sharing resources, commoning involves a self-defined community, commoners who are actively engaged in negotiating rules of access and use or the making of a social contract. As historian Peter Linebaugh argues, commoning is a verb, a social practice: “…commons are not yet made but always in the making; they are a product of continuous negotiations, reclaiming, reproducing in common. Spaces of commoning, then, are a set of spatial relations produced by practices that arise from coming together. They are the spaces of encounter and mediation of differences and conflict. They are also a means of establishing and expanding commoning practices.”1

Her phobia is infection,

she needs one to survive

It's her built-in protection,

without fear she'd give up and die

Jules van den Langenberg

Germfree Adolescents

Group portrait at The Factory group shot by Stephen Shore.

Jules van den Langenberg

Germfree Adolescents

The Dysfunctional Family of The Commoners’ Society, Instagram account @thecommonist, 2019

During one of the first gatherings of The Commoners’ Society, a Temporary Master running from 2018-20 at the Sandberg Instituut, I found a group of makers and thinkers that seek to bridge the individual and the communal by developing local practices that remain critically aware of the global context. Their very first thoughts and works articulated at this meeting, focussed on finding alternatives to a post capitalist society. The different interpretations of commoning became apparent in hearing ideas ranging from a good intentions scanner, mobile open stages to be used by subcultures within a community and developing a common sans typeface for neighbourhoods. Is this a Master program in compassion? Will they operate as a collective true to the practice of commoning? How do you initiate a project comprised of individuals and evoke communal authorship at the same time?

One could draw parallels between The Commoners’ Society and Warhols’ collective, The Factory, in which the production of varied artistic outcomes was generated through a collective effort. As the name of this studio implies members of The Factory were primarily concerned with mass production and commerce and in negating what constitutes originality in art. The uniqueness of art works was questioned by manufacturing identical paintings and sculptures in unlimited editions. The Factory emerged in the midst of the Punk era where artists, fashion designers and musicians found a common space in protest against Thatcherism, deregulation and the spread of Neoliberal politics. Germfree Adolescents, the debut album of English Punk band X-Ray Spex, released in 1978, is one example of this protest. The album referenced the increasingly scripted nature of society and identity, as the cover art illustrates, depicting adolescents encapsulated in test tubes, an early example of the filter bubbles that define user identities on social media

He's a germ free adolescent,

cleanliness is her obsession

Cleans her teeth ten times a day

Scrub away, scrub away,

scrub away the S.R. way

Jules van den Langenberg

Germfree Adolescents

X-ray Spex, Germfree Adolescents (1978), album cover

This idea is still relevant today, although in different guises, mobilised in the movements and agendas of a younger generation of artists, designers and other cultural workers responding to the conditions of precarity as they manifest in a lack of gainful employment and accessible housing. This energy is also directed against the art market, where the art object is commodified along similar lines to Simons' product lines for Calvin Klein. Ultimately, he and his team were remaking commonplace garments (like jeans and underwear) as designer fashion items. However, in the act of doing so attempting to "fuck with Americana”1 as the process was dubbed by collaborator Sterling Ruby. It is therefore not only a protest, but a form of organisation, and this, I think, is central to the idea of commining. Viewed in this light, could the work of Raf Simons for Calvin Klein be considered as a post-capitalist gesture?

He's a germ free adolescent,

cleanliness is her obsession

He's a germ free adolescent,

cleanliness is her obsession

He's a germ free adolescent,

cleanliness is her obsession

He's a germ free adolescent,

cleanliness is her obsession

Cleans her teeth ten times a day

Scrub away, scrub away, scrub away the S.R. way

The experimental educational form of the Temporary Programmes, under development since 2007 at the Sandberg Instituut enables both the Instituut and its contributing programme directors and participants to act upon urgent societal issues over an intensive two year period. This temporary timeframe requires close engagement with the research topic at hand, and collaboration between the individual members of the group, if any valuable results are to be achieved. In many ways this institutional agility is admirable as it enables different voices to take centre stage and enter a research and development period on speed mixed with acid. The rapid succession of programmes is known in advance to the public, students, tutors and others involved, similar to the biennial structure. As Editor-in-chief of architectural magazine Volume, Arjen Oosterman puts it, commenting on the criticism levelled at Biennials:

"The biennial as format and phenomenon was declared dead or obsolete time and again, it was discarded as

commercial, promotional, touristic, capitalistic, wasteful, white supremacist and what not. In the end, that is not the issue. The issue is the tension between expectations and pretension, between agency and result."2

Jules van den Langenberg

Germfree Adolescents

Calvin Klein ad campaign with Andy Warhol's Elvis series.

The appointment and departure of Simons at Calvin Klein took less than two years, making for an interesting, albeit coincidental, comparison to the structure of art and architecture biennials. What opportunities would be brought about by a company or organisation that appoints their creative directors for a standardised two year period? Could the fast paced changes of creative directors in the fashion industry then be labeled as another act of commoning? Organisations could work on the basis of having a library cataloging their institutional history, to be delved into, elaborated upon and propelled forward by each new director, none claiming the exclusive state of authorship.

Hence, the question remains, are these young makers and thinkers of The Commoners’ Society speedy enough to consolidate and release their thoughts and works—as agile as a creative director or a biennale curator able to strategically use the mechanics of a scripted environment— or seduce the public and current status quo to engage and develop alternate futures with them? Will this time period be productive as an act of commoning?

- Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-pvh-results/pvh-falls-short-of-revenue-estimates-on-softness-in-calvin-klein-idUSKCN1NY2T5 ↩

- DIA:Beacon website: https://www.diaart.org/program/exhibitions-projects/andy-warhol-shadows-exhibition-218 ↩

- Warhol, Andy (1975). The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again). New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich ↩

-

Baldauf, Annette. Spaces of

Commoningin Spaces ofCommoning: Artistic Research and the Utopia of the Everyday, eds. Anette Baldauf, Stefan Gruber, Moira Hille, Annette Krauss, Vladimir Miller, Mara VerliÄŤ, Hong-Kai Wang, Julia Wieger (Berlin. Sternberg Press, 2016) ? ↩ - Panel discuss with Sterling Ruby and Raf Simons at DIA:Beacon on YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vduXOEYNag0 ↩

- Oosterman, Arjen. "Editorial: Agnecy" in Volume #54: On Biennials (Amsterdam. Archis/Amo, 2018) ↩

About the author

Jules van den Langenberg (Lennisheuvel, 1988) is an independent curator, exhibition maker and writer based in Amsterdam. His projects derive from ongoing dialogues with artists, architects, designers, cultural institutes and educational programmes. Key to his practice is redefining notions of representation, scripted spaces and talent with a focus on—but not limited to—the cultural field. Van den Langenberg collaborated amongst others with Sandberg Instituut, Creative Industries Fund, Van Abbemuseum, Studio Makkink&Bey, Studio Edelkoort, Het Nieuwe Instituut, Thomas Eyck, TextielMuseum, Simon Becks, Wouter Paijmans, Saskia Noor van Imhoff & Arnout Meijer, Brecht Duijf & Lenneke Langenhuijsen, Studio Minale-Maeda, Lernert&Sander, Sander Manse, Bruno Vermeersch.