Lara Staal

Letter to Thomas Spijkerman

Dear Thomas,

Thanks for your letter, which I read with great interest. The questions with which you open really speak to me. First of all the fact that you donãt start with art for once, but with human beings. And then the question of what human beings can do, should know, and above all what they should do.

Iãm glad you didnãt start with art because I sometimes get the feeling that people who work in the arts canãt talk about anything anymore without constantly wanting to make a sometimes artificial connection with the arts. As if, in the wake of the funding cuts of 2013, we still feel the need to explain that there really is a link. As if we ourselves are not entirely convinced that art and society are irrevocably connected with one another.

You describe how you were born into a world that had already been worked out. Describing the state of the world, as you do in your letter, has everything to do with art in my view. Being able to describe reality requires imagination. Since we are ourselves part of the world, we canãt adopt a neutral position from which we can oversee everything; for that we need imagination. We have to be able to imagine what someone else in our position would see. Only in that way can we become aware of our own subjectivity. And we have to be able to imagine what the history books have ignored or what we have forgotten over time.

Yet there is also something dubious about that act of describing the world. Because by describing it, you colonize in a certain way. At the same time, not wanting to describe it may be even more problematic because that means you are embracing a kind of powerlessness. Information that refuses to become a story makes it impossible to take up a position. So itãs a matter of describing the world over and over again and simultaneously remaining open to the criticism and blind spots that every description entails. Thatãs how I see our letters, too. As an exercise in getting closer to the truth without ever wanting to reach a single definitive version.

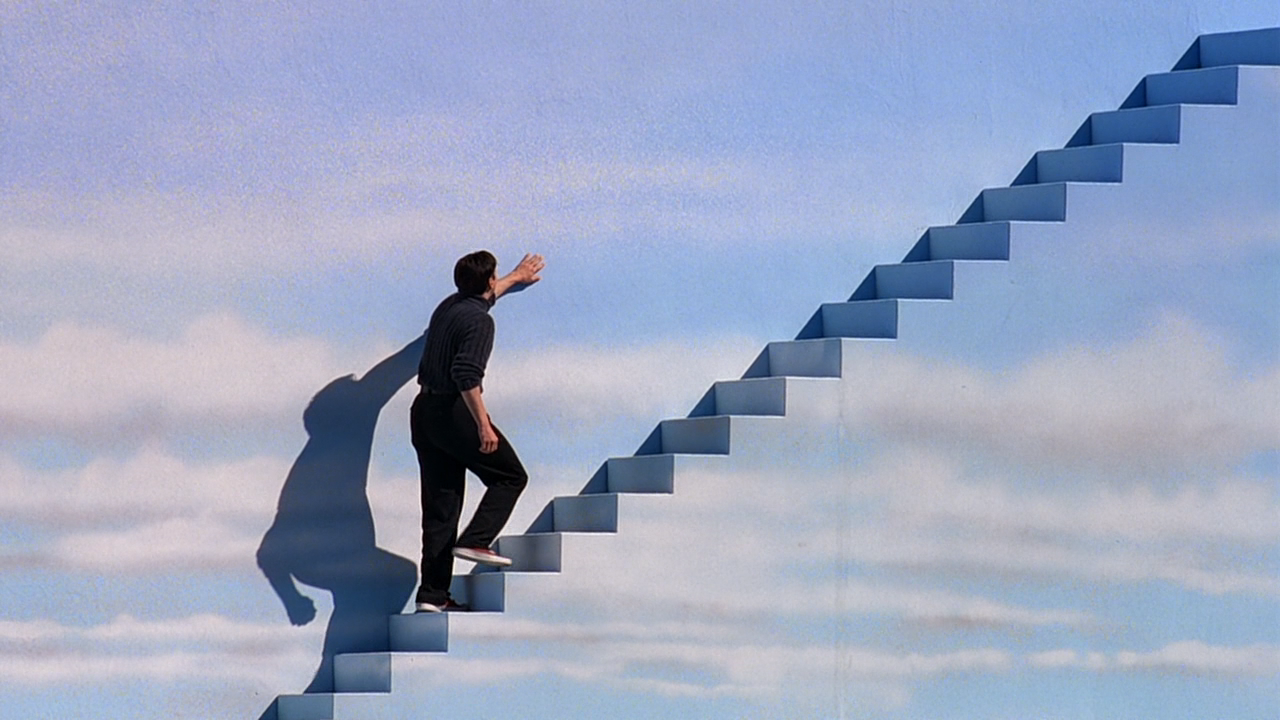

Your description of the (Western) world does indeed sound like a Truman Show consisting of a society dominated by industrial agriculture, McDonaldãs and plastic bags. On my darker days I recognize myself completely in your depiction of a sort of deranged consumer machine in which everything is for sale, no one is happy, and the riches of the earth are slowly but surely being devoured, spoon by spoon, as if there is no tomorrow. But that position would be too facile. We are not born neutral, nor are we passive observers of a purely tragic spectacle. We come into the world with a particular position, history and baggage. From the very first day we are participants and our actions affect the way things work, for which we should take responsibility.

From the architecture of a building, to the way a park is laid out, to the bakerãs signboard: everything is unquestionably political. Because behind those choices lie ideological views about whom these spaces are conceived for, who is welcome in them and who not, and how we as human beings want to behave vis-û -vis one another. If you are keen to change some aspect of that, I donãt think youãll necessarily have more success as a politician than as an artist, journalist, baker, activist, or architect. Thus I question your division between art and politicsãan antithesis that keeps cropping up in the debate about the value of political art. As if art remains stuck in the realm of fiction while politics can transform reality at will. But tell me this: which politician genuinely feels that his or her actions have a direct impact on the dominant systems around us?

Since the 1990s we have surrendered to neoliberal capitalism. The economy is completely globalized and we have handed power over our own infrastructure to market forces. To the point where we are all a bit dismayed by what we see: hospitals going bankrupt, academics protesting because they canãt get tenure anymore, the growing threat of global warming, Yellow Vests claiming that everythingãs become unaffordable and that for them there is no longer any prospect of better times.

I fear that most politicians donãt feel that they are able to overturn neoliberalism and take up the reins again. And perhaps thatãs just the problem. The system has spiraled out of our control and we no longer know how we can regain influence over our own living environments. So I donãt think that Iãd be able to accomplish much more as a politician than as an artist, writer, teacher, or activist. Itãs true that we employ different strategies and itãs important to find a strategy that suits you and to employ it as forcefully as possible, to maximize the chance of striking a chord.

The millennial predicament you describeãin which we can keep abreast of whatãs wrong in the world 24/7, we are constantly told that we must dare to think big and that we can become anything we like and yet there are so few concrete instruments to help us transform daily lifeãis indeed a complex cocktail. Thereãs an all-pervasive sense of powerlessness. To my mind that has something to do with the way we have come to value results. Nowadays we donãt feel weãve achieved anything unless we have concrete results to show for it: the so-called impact disease. In my view thatãs a structural simplification of how a democracy works. You canãt expect that an article, art project, or political intervention will have an immediate, clearly demonstrable effect. Thatãs a form of megalomania! A democracy is made up of people who take action every day. Sometimes they work against one another and sometimes with one another. What effect an action or vision has depends on the momentum and on the circumstances in which it is shared. The recent occupation of the Maagdenhuis turned into a worldwide ãRed Squareã protest in which students and staff objected to the neoliberal policies of their universities. The hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was tweeted after the acquittal of George Zimmerman, the policeman who shot and killed teenager Trayvon Martin in 2012, and so grew into an international protest movement. Dissatisfaction swells, someone comes up with a symbol or a phrase that succeeds in channeling the frustration and suddenly there is the possibility of a movement.

I cite the following metaphor frequently, but itãs the clearest way of explaining things. The philosopher Rebecca Solnit talks about the creation of a fungal network. Thatãs the daily toil driven by ideals. Teachers, social workers, care providers, artists, academics, journalists, politicians, lawyers, and activists all contribute to an underground fungal network with their daily activities. Not always visible to the outside world, but nevertheless solid. At the moment when there is sufficient momentum and various events interconnect, it may rain and a mushroomãin the form of a revolutionãmay rise up. Whether this will happen cannot be predicted beforehand. Often several factors are necessary for that; but at the moment when the discontent is sufficiently widely shared, the existence of such a fungal network is vital. It is precisely because it has lain in wait there all that timeãgrowing steadily all the whileãthat opposition is able to manifest itself rapidly and efficiently.

So no, we canãt become Nelson Mandela just like that. Besides, Nelson Mandela spent 27 years of his life in prison. Many of us are not capable of that and nor is it necessarily worth emulating. We canãt become everything we want to become. We are defined by origin, age, health, color, gender, and geographical location, but we are also not entirely powerless. The main thing is to find a domain in which you are best able to communicate the values and ideals in which you believe.

How buildings, and occupations such as postman, lawyer, or baker function is not set in stone. Itãs a challenge to keep invoking the scenario that determines our daily life. Things appear to us as if they are immutable. Which is why we should invest much more in teaching people about past victories. There was a time when we lived in a world without pensions, without female suffrage, without legalized abortion, without insurance, and with slavery, torture, and forced marriages. All those things have been achieved or won in the past by carefully nurtured fungal networks of people who did not resign themselves to the Truman Show, but kept believing in the changeability of the then prevailing scenario.

As artists, therefore, we can most certainly influence our surroundings. The problem is that art is often immediately recognizable as art and is thus to a large degree rendered harmless. That is the price that we, the arts sector, pay in order to be allowed to occupy a position of exceptionality. The arts are still governed by different rules. We can organize a fictional lawsuit against Europe, erect a memorial to the death of democracy, or establish an alternative parliament. We donãt need to observe the same protocols as a political organization; after all, itãs art. The downside of this is that we are immediately relegated to the ãartã corner. Art is allowed to confuse, provoke, and set people thinking, but fortunately has no real implications; itãs ãonly artã.

This makes Reinventing Daily Lifeãs exploration of how artistic forms might fully infiltrate and blend with daily life a very interesting challenge, because it does indeed turn its back on the Romantic ideal of the artist as the sole auteur of his or her own masterly creation. Instead it looks at how, in dialogue with society and with people working in different domains, artistic practice could operate in the heart of society.

Nevertheless, Iãm not sure about equating artists with the practitioners of other occupations, based on the notion that what we most need is ãconnectersã with a moral compass. For me, artistic practice is more than connecting and behaving morally. And although many other occupations work with and from imagination, I still think that artists are always able to add something vital. As soon as you operate in the domain of the arts, the parameters are different. Whether you walk into a youth theater school, work in a visual arts center, or visit an artistãs studio, there is still generally a sense that the rules are negotiable there. People who work in the arts do not by and large like fixed patterns. A constant rethinking of structures goes with the territory. That capacity to repeatedly rethink things and never take them for granted, and the opportunity to operate beyond expectation, is sorely needed in a world dominated by a craving for safety, fixed identities, and certainty.

Moreover, theater involves something else very special: the idea of the ãrehearsalã or the ãpractice.ã In a defined space, a new social order can be tried out. Something that can act as a horizon for society and shatter the idea that we ãlive in the best of all possible worlds.ã This exercise may have an even greater effect outside the black box. That is the investigation that Reinventing Daily Life embarked on. Bystanders donãt know that itãs ãartã so the proposalãwhatever the reaction to itãis taken seriously. It is instantly part of reality. This is the notion of the ãpre-enactment.ã We rehearse an alternative reality as long as society is not yet ready to allow it to become reality. We rehearse in anticipation...

As far as Iãm concerned, this age needs artists more than ever, people who do not accept the Truman Show and repeatedly demonstrate that the world in which we live could also be quite different. Art as an instrument of emancipation, continually reminding us that things really can be changed. Not in a predictable way with measurable results. Being part of a democratic order quite simply means that things seldom develop in a straight line. But that conclusion can never be a reason to abandon it. Now more than ever we are in need of alternative imaginings, since society appears to have seized up. We know that the current system has ceased to function, but we havenãt yet found the first glimmerings of an alternativeãa bit like a cartoon character who runs over the cliff edge and for a while continues to walk in a vacuum before falling to earth. Meanwhile the media, politicians, and the entertainment industry demonstrate how theatricality and spectacle serve to hide rather than address this status quo. That is why we need political artists who deploy their imagination not in fleeing the current reality, but in tackling it, criticizing it, intervening, and developing alternatives.

Art cannot do everything and nor is it free. Any more than any of us is. Making art is never without consequences. Creating new references, tackling abuses, provoking the public, together looking for alternatives: none of that has anything to do with freedom, but with assuming responsibility for the world in which we live. And a good thing too, for nothing is more boring and inconsequential than free art. Free, after all, means without consequences. Whereas we are looking for strategies for intervening in the Truman Show, as a dogged reminder of the fact that it doesnãt have to be like this.

Warm regards,

Lara

Lara Staal

Letter to Thomas Spijkerman

The Truman Show (1998), Peter Weir.

About the author

Lara Staal (Zwolle, 1984) is a researcher, writer and curator. She graduated in Theatre Pedagogy and Theatre Studies and worked as a programmer at Frascati (Amsterdam). She is currently working as a dramaturge for the Mû¥nchner Kammerspiele and curates social-political programs for NT Gent. She writes for magazines such as Rekto:verso, Theatermaker and Etcetera.